|

Up until the year 1800

virtually nothing was known or recorded of the

features and nature of the interior lands of

Michigan although the waterways and shorelines

had been mapped to some extent, but only for the

purposes of the explorers and traders and the

locations of Indian villages and the

identification of those Indians.

The first white man to have

reached Michigan was Jean Nicolet, a French

explorer. He traversed the shores of Lakes

Huron, Michigan and Superior, and then returned

to the Straits of Mackinac. The two main Indian

Centers were at Michilimackinac (Mackinaw City)

and St. Ignace. Nicolet went back to France and

then returned in 1604, with a Jesuit, Father

Claude Dablon, and a small force of French

soldiers.

To the northeast, in New

France (Canada), the area was controlled by the

Algonquian Indians, in the northern part of the

Lower Peninsula the Ottawas were in command. The

Ojibwas occupied the Upper Peninsula, while the

Pottawatamies held the southern part of

Michigan. Father Marquette established a

mission at St. Ignace and also operated out of

Old Fort Mackinac. A small settlement was

established at the head of the rapids on the St.

Mary's River and became Sault Ste. Marie. A

trading post was set up on Mackinac Island and

was accepted by all Indian factions as neutral

ground. Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, the French

colonial governor of North America, in 1694

moved from Nova Scotia to Old Fort Mackinac and

took command. In 1701 Cadillac moved much of the

garrison at Fort Mackinac to Detroit, where the

outlet of the upper great lakes flowed from Lake

St. Clair into Lake Erie.

In 1760, near the end of

the French and Indian Wars, Major Robert Rogers

made an expedition westward to capture French

forts for the English. He met with Pontiac,

Chief of the Ottawas, to gain their assistance.

The Treaty of Paris, signed in 1763, ended the

French control in Canada and to the west.

Using the confusion that

followed, Pontiac took this as an opportunity to

regain the Indian domination of their lands. He

formed an alliance of the Algonquian nation,

and the Ottawas, being reinforced by Wyandots,

Pottawattamie and Ojibwas, stormed Fort Detroit

on May 10, 1763. Pontiac was unsuccessful and

retired to the Maumee in Ohio. From here he

continued his attacks and destroyed and

massacred the garrisons of Sandusky, Presque

Isle and Old Fort Mackinac. In 1780 Old Fort

Mackinac was moved to Mackinac Island.

During the War of 1812, an

American force under General William Hull

surrendered to a much smaller Canadian garrison

at Fort Detroit. In 1813, the Americans suffered

another defeat in a battle on the River Raisin

near the site of Monroe. Finally, with the

victory of Captain Oliver Perry on Lake Erie,

General William Henry Harrison's forces were

able to push back the British who burned Fort

Detroit and retreated into Canada. Harrison

pursued them and defeated them on the River

Thames north of the present Windsor, Ontario. In

this battle Indian Chief Tecumseh was killed.

In 1803 Ohio was admitted

as a state. It included a large area of

undeveloped land (Michigan, Wisconsin, and part

of Minnesota), and was called the Huron

Territory. The area in the extreme southern part

of what is now Michigan began to become

developed first around Detroit, Monroe and

Tecumseh and then westward along the old Sac

Indian Trail between Detroit and Chicago. By

1833 there were only scattered settlers,

trappers, etc. in the extreme southeast of

Michigan. The U.S. Government sent a regular

survey team to that area and a coordinate system

was set up for the subdivision of land. As of

1835 the whole area north and west of Saginaw

was still just a blank on the map. Northern

Michigan was a wild and undeveloped area.

However, a few settlers were beginning to drift

into the Southern Michigan area which would

later become known as Ridgeway Township.

Lower Michigan sought

identity as Michigan Territory and admittance to

the Union. When this succeeded, Ohio was forced

to cede that area and the surveys of the Public

Domain were just underway so that the southern

boundary of Michigan, as it was then defined,

ran eastward and would have cut the new

settlement of Toledo in half east and west. A

reference to a map will show that the east

portion of the south boundary of Michigan

extends farther south than the west portion. The

eastern line extended south ten miles. Ohio and

Michigan went around on this and it looked like

the River Raisin would become a battleground in

a two state civil war. Finally Ohio offered

Michigan the northern part of the Huron

Territory (the Upper Peninsula) in return for

the south five mile strip in the Toledo area.

Also, Michigan would administer the balance of

the Huron Territory (Wisconsin and part of

Minnesota).

Michigan was admitted to

the Union in 1837 and then came the chore of

organizing it and subdividing it into counties

and townships for administration, with Detroit

being named the state capitol. The northern part

of the Lower Peninsula was not surveyed until

the early 1840's.

General Lewis Cass became

Michigan Territory's first governor. He urged

the building of five military roads in Michigan

but only three were started one north to

Saginaw, another west to Muskegon and the third

followed, the Sac Indian Trail to Chicago

(present U.S. Highway 12).

In 1840 the first state

geologist, Douglas Houghton, and John Burt, a

government surveyor, went into the western end

of the Upper Peninsula and the Keweenaw where

Houghton delineated the vast copper and iron

deposits of the area. Burt made his plans for

the survey which was carried out from 1843 to

1845.

With the Treaty of LaPointe

in 1843, this area was ceded to the U.S. by the

Ojibwas (Chippewas) and the first copper mine

was opened on the north end of the Keweenaw in

1843 with Fort Wilkins being established at

Copper Harbor to protect the miners.

In the 1840's and 1850's

railroads were being experimentally pushed

westward to Ohio and south into the

plantations. The first railroads were poorly

constructed, narrow gage and only took the most

accessible routes, often bypassing more

lucrative areas. The first big trade was in

passenger service and for the mails.

At the time of statehood

(1837) there were an estimated 90,000 people in

the whole territory. By 1850 there were just

fewer than 400,000. By 1860 the population had

swelled to 750,000 and by the end of the Civil

War, in 1865, the number was about one million

and Michigan had furnished just fewer than

100,000 men to the Union armies. Railroads had

been established to Detroit and across the lower

end of the state to Chicago. A few branch lines

extended north for short distances to some of

the numerous but small communities.

After the Civil War nothing

eventful took place other than the nation trying

to readjust after that terrific upheaval. Then

two unrelated events took place. On October 7,

1871, a forest fire started in the vicinity of

Peshtigo, Wisconsin, near Green Bay. On October

8, 1871, the great Chicago fire started, which

leveled practically the whole city. While 400

lost their lives in Chicago, some 1200 died at

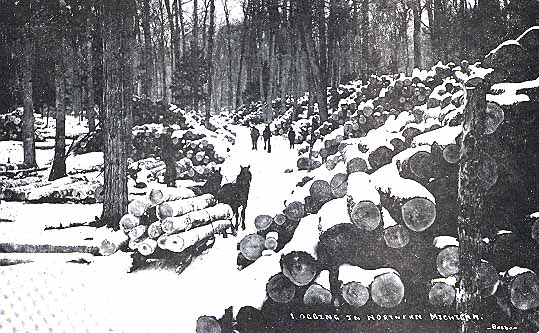

Peshtigo. All of a sudden the vast white pine

stands of Lower Michigan and that of Northern

Wisconsin brought to attention by the Peshtigo

conflagration was the center attraction and the

mad rush was on for the lumber to rebuild

Chicago, first, and the burgeoning demands of

the rapid growth and settlement of the Midwest.

The first sawmills sprouted up along the shore

of Lake Huron around the "thumb", into Saginaw

Bay and on up towards the Straits of Mackinac.

Water was the prime source and means of

transporting the pine logs which floated

readily and for the shipment of lumber on barges

and hookers around into Lake Michigan to Chicago

and to most other ports along the Great Lakes.

The vast timber stands

which were proclaimed as being of a size to last

"forever" were largely depleted by 1890. During

the two decades between 1870 and 1890 the rush

to the north brought multitudes of people who

settled there and benefited by the heyday of

this new industry and railroads extended into

all parts of Lower Michigan and small towns

cropped up allover this area. Lower Michigan did

not have a corner on the white pine stands in

Michigan and in the 1870's the more venturesome

timber men moved into the Upper Peninsula and

exploited the heavy stands which occurred in the

eastern and western portions.

With the first development

of the copper lodes in the extreme northern tip

of the Keweenaw in 1843 the occurrence was

traced in a southwesterly direction for 100

miles with the significance dwindling in that

direction. By 1850 mining companies were

organized and controlled all of the property.

The iron mines on the Marquette range were being

developed and the Menominee and Gogebic areas

were being explored. At the time of the Civil

War most of the world's copper and nation's iron

was coming from Northern Michigan.

The basic connection

between the Upper and Lower Peninsulas was that

of railroad traffic which was transferred across

the Straits of Mackinac on huge rail car

ferries, the most memorable of which was "Chief

Wawatam". When automobiles came into existence,

the cars would crowd into any available space on

the ferries. Later, smaller ferries were built

for automobiles and passengers and then

trucking. Still later, the big suspension bridge

was constructed between Mackinaw City and St.

Ignace and rail traffic dwindled to a virtual

standstill.

This, then, together with

reference maps, should give you a pretty clear

picture of what Michigan was like when the

family of James Getty came on the scene and for

a time thereafter. It all began less than a

century and a half ago.

|